|

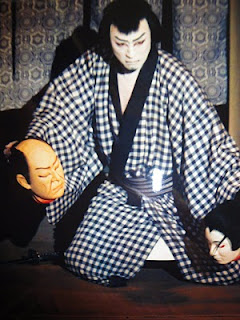

| A scene from Yotsuya Kaidan-Chushingura, described below. |

Weduesday's weather was mild, upper sixties, but I spent the day in the Waseda library. I almost didn't get there though because when I got on the train platform at Kichijoji to wait for the Tozai Line, the train never came. I then realized that the loudspeaker voice I kept hearing was saying that there'd been an accident at the Mitaka Station and no trains were running on these tracks. I asked a burly guy next to me how I could get to Waseda but his Japanese sounded like Neanderthal. So I moved away and asked a well-dressed woman, and she reminded me that I could take the Chuo Line to Nakano and switch there for the Tozai. I had forgotten this simple fact. However, the fact that the Tozai wasn't running through Kichijoji meant that any train I boarded would be so crowded that I'd feel it in the kishkes. Which I did.

There were other complications at Nakano, but I did eventually manage to reach Waseda, only to have the red alarm go off when I put my electronic passcard on the meter to leave the station. It said I was short 150 yen, so the station guy, who is posted at the gate waiting for just such moments so he'll have a story to tell his grandkids, jumped into action and forced me at gunpoint to pay up what I owed. Just kidding. But in Japan, if your ticket or card registers short when you exit the station--you always go through an electronic machine on both entering and exiting--you simply pay the man in the booth the balance. Still no one wants that alarm to sound and the automatic gates to suddenly open at your midriff, barring your passage. It's just too hazukashii (embarrassing) for words.

On Wednesday, I received some depressing family news from home. Let me tell you, it's bad enough when you're by yourself and learn something unpleasant. It's far, far, far worse when you're over 13,000 miles away and can't do anything except instant messaging or Skype. Ugh.

I spent several hours working in the small Shochiku Otani Library, not far from the Kabuki-za. This is as good a place as any to return to that theatre for more videos of its fabulous interor. First is a brief one of entering the theatre to find my seat. Then we take a tour of the second floor lobby areas, replete with souvenir shops. Then we go outside to watch as the crowd from one show lets out, while another crowd waits to get in and a policeman keeps the area clear.

Here are some stills of the Kabuki-za experience.

Outside the Kabuki-za between performances.

The electronic counter marking the days until the Kabuki-za's present existence comes to an end.

The ticket window.

People waiting for the show to begin.

The April 2010 programs. There are usually two a day. Because it was the theatre's final month, three were offered.

The traditional signboards outside the theatre. New paintings are prepared each month by artists of the Torii school.

The old dame, in her final days of glory.

The crowds, the crowds.

Entering the theatre.

In the front lobby.

Entering the auditorium.

The hanamichi runway.

A view of the interior.

The draw curtain (hiki maku) whose stripes are often used as a symbol of kabuki.

From the rear of the hanamichi to the stage.

The agemaku curtain through which actors enter the hanamichi.

The Earphone Guide booth. You can listen to explanations in both Japanese and English for a little more than $6.00 for the day.

A chopstick craftsman sells his wares in the souvenir area.

More kabuki and Kabuki-za related souvenirs.

Shops galore.

More souvenirs.

Souvenirs for your tummy.

The counter where you make meal reservations.

Now to get back down to earth. At the library, I spent several hours searching through old theatre programs from the 1950s and requesting copies to be made. As I've said before, this place charges over $.50 for a single page, and, as you can imagine, I had dozens and dozens of pages to copy. I'd finish a volume, fill out a form saying which pages I needed, put slivers of paper at the spot in the volumes where the copying was to begin, submit it to the librarian, and then return to look for more. When I left at 1:30, the copies still hadn't been done. The pace is glacial! The librarian promised to have them ready for me when I returned next week, when I'd begin another round of requests. How inefficient is that? And at those prices?! Here's a video of the area outside the building.

I saw the second of this month's three programs at the Kabuki-za. It began with The Village School (Terakoya), which I translated and directed back in 1976 at Brooklyn College. Jimmy Smits--yes, that Jimmy Smits--played one leading role, Matsuo, and another then student, Elliott Nesterman, with whom I've recently reconnected through Facebook, played the other, Genzo. My son, Justin, played the little prince whose life is endangered. The play is among the most feudalistic in the repertoire, being about a man who must sacrifice his own little boy's life to save that of another child because of a secret obligation to the saved boy's father. This mid-18th-century play--adapted from the bunraku puppet theatre--was forbidden by the Occupation censors shortly after the war because it was deemed to uphold the predemocratic system of obligation over human feelings. But it was eventually allowed performance and remains one of the most frequently produced plays in kabuki. It starred Matsumoto Koshiro IX as Matsuo and Kataoka Takao XV as Genzo. These are two of Japan's greatest actors. They brought out all the play's weepy, semi-tragic overtones with their powerful performances.

The second play on the bill was a famous scene from The Three Kichisas (Sannin Kichisa), featuring another lineup of outstanding players, Onoe Kikuguro VII, Ichikawa Danjuro XII, and Nakamura Kichiemon II, as three rogues named Kichisa who meet by chance one night on a riverbank and become blood brothers. One of them dresses as a high-class young woman as a ruse to rob (or kill) people, another is a sort of priest, and the other a rascally samurai. It's an atsmopheric piece from the nineteenth century showcasing three popular actors' bravado personalities.

Finally, the 79-year-old master actor Sakata Tojuro IV (formerly known as Nakamura Senjaku and Nakamura Ganjiro), who plays mainly women and handsome young men, danced the classic Wisteria Maiden (Fuji Musume), a frequently seen dance with only a wisp of narrative, designed chiefly to show off the dancer's skill and charm. The stage is gloriously adorned with hanging wisteria blossoms, which are also embroidered on the several kimonos the dancer displays during the course of the dance, as an onstage orchestra accompanies his movements, singing poetic lyrics. Tojuro seemed weak the other day playing the dramatic role of Sagami in Kumagai's Battle Camp, but, despite his age, he somehow managed to carry off the illusion of a beautiful young woman, recapturing to a remarkable degree the sensual beauty he was famous for in his youth over half a century ago. Kabuki's white and pink makeup helps, of course, but even makeup can go only so far.

The news from home had robbed me, not only of appetite, but of energy, and I felt an overwhelming drowsiness during The Village School, forcing me to pry my eyes open so as not to miss the highlights. Also, sitting in the second row during a performance with the theatre house lights on (a common kabuki convention) meant the actors could see me napping if they looked. Kabuki actors often play straight out, so the chance of being spotted kept me from falling into a truly deep sleep. I kept feeling my head snap whenever I fought off Morpheus' grip. Know the feeling?

Despite the Gordian knot in my stomach, I had to meet my old friend, Richard Emmert, for dinner in Kichijoji. Rick is a brilliant ethnomusicoligist who teaches at Musashino University, not far from the university I'm staying at this month. He runs a company called Theatre Nohgaku that teaches noh to foreigners, and offers workshops every year in the U.S., usually at Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania. Rick is also a pioneer in the production of noh plays in English translation. Since the meal was mostly niblets of grilled chicken, I managed to get some of it down (not the chicken cartilage, though), but the best part of the evening was sharing backstage stories about kabuki, noh, and kyogen with this wonderfully knowledgeable expert.

Since I wasn't feeling too hot, I decided to stay in and rest all of Thursday. Actually, I spent the day sorting and labeling hundreds of Xerox copies, which were beginning to get mixed up. This revealed a few gaps that I'll fill in when I get back to the library. The evening was spent with old friends, Reiko and Tsuyoshi Hayakawa, with whom I dined on tenpura in Shinjuku. Reiko was a 19-year-old when I gave her and a friend private English lessons in 1963. You wouldn't believe how youthful and attractive she still is if I told you. So here's proof positive.

Today, Friday, I went to kabuki at the Shinbashi Enbujo, the theatre to which mainstream kabuki will move next month when the demolition of the Kabuki-za begins. As this video and the next show, it's only a short walk from the Kabuki-za. Shinbashi is the name of the local neighborhood, famed for its geisha culture, and Enbujo is written with the characters for theatre-dance-place. It was first erected in 1925 and has been rebuilt several times since. Like the Kabuki-za, it was bombed toward the end of WW II, but it was rebuilt sooner than the Kabuki-za, which waited until January 1951 before reopening. It's now part of a high-rise office building, much as the Kabuki-za will be one day. There's nothing uniquely interesting about its exterior, just another brick and concrete structure, and its modern interior, seen in this video, while attractive and up-to-date, lacks the rich atmosphere of the Kabuki-za, now soon to disappear. I'm sure the new Kabuki-za will be similarly antiseptic. Here's my video tour of the lobbies.

The production was a play first produced in 1980, revived in 2003, and now given its third production. It is a conflation of two of kabuki's greatest plays, Ghost Story of Yotsuya (Yotsuya Kaidan) and The Treasury of Loyal Retainers (Kanadehon Chushingura). The latter was originally a bunraku puppet play, written in the late 1740s, and soon adapted by kabuki. Ghost Story of Yotsuya is one of many spinoffs of The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, but over the years its connection with the older play gradually weakened. It is a hair-raising ghost story about an evil former samurai who finds himself in straitened circumstances and betrays his wife, who takes a poison that horribly disfigures her before she dies and returns to haunt her faithless husband. It is performed with a mixture of gritty realism, striking stylization, and special effects. The Treasury of Loyal Retainers is a history-style play based on an actual vendetta that occurred in 1702, although censorship practices forced the authors to set it in the distant past. Its revenge story is iconic in Japan, so much so that it was strictly forbidden by the American censors for fear it might incite the defeated Japanese to seek vengeance on their victors. You can read about this in my adaptation of Okamato Shiro's

The Man Who Saved Kabuki: Faubion Bowers and Theatre Censorship in Occupied Japan.

Here are some publicity photos from the production. They're photos of photos, not scans, so their quality is not of the highest. They should give you an idea of the style and look of the show.

The great actor, Ichikawa Ennosuke III, now unable to act because of illness, did the adaptation and directed it. His company is composed of actors who are highly trained in kabuki performance but who don't belong to the major kabuki families, and who don't bear the household names of people like Ichikawa Danjuro, Nakamura Kichiemon, Matsumoto Koshiro, and so on. Ennosuke, one of the most innovative kabuki actors in modern history, often produces spectacular Las Vegas-like kabuki productions of new plays, which he calls Super Kabuki, but, except for some special lighting and stage effects, was rather faithful to the traditional kabuki conventions, even though the original plays on which it was based were cut and conflated considerably to fill a five-hour program. A full-length version of The Treasury of Loyal Retainers would still have to cut one or two acts to fit the parameters of a five-hour matinee followed by a five-hour evening performance. It was well done, and represented the essence of Ennosuke's motto: Speed, Spectacle, and Story.

Sign leading to the Shinbashi Enbujo.

Interior view of the Shinbashi Enbujo.

A view of the hanamichi.

View of the glass wall over the stage.

The formal drop curtain usually used before nontraditional plays. However, during the course of this production, the standard striped draw curtain was used between each scene.

Scene in the lobby.

Shinbashi Enbujo frontage.

No comments:

Post a Comment