|

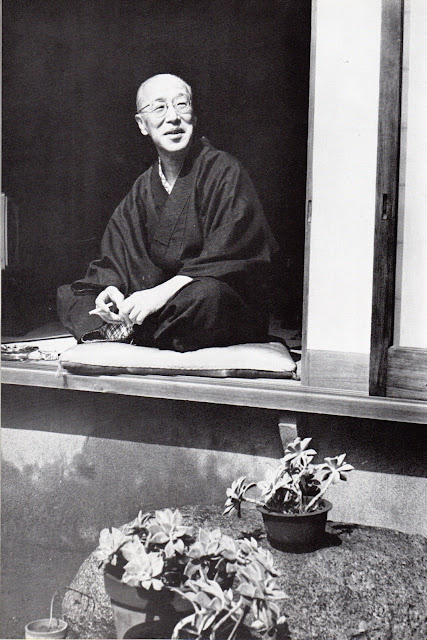

| Leonard Pronko. If anyone can identify the conference at which the photos of Leonard were taken (the workshop one below will help), please notify me/ |

Leonard Cabell Pronko (1927-2019) passed away on November 27. A professor at Pomona College, Claremont, CA, he was one of the West's leading experts on kabuki, although he was also a scholar of modern French theatre. He not only wrote about kabuki in books and articles, but actually practiced it, giving performances as well as directing college students in traditional kabuki in English, Western plays written for kabuki-style performance, and classics, like Macbeth, conceived in kabuki style. He was a larger-than-life presence, a charismatic teacher, world traveler, and the warmest of friends.

|

| With Leonard and another scholar. I'm in the middle. Please let me know if you recognize the man on the left. |

I first met him in Tokyo, in 1963, when he was on a Guggenheim research trip to study Asian theatre, and I was an East-West Fellowship student studying kabuki for my MFA at the University of Hawaii, where I would do for my thesis--a production of Brecht's

The Caucasian Chalk Circle in kabuki style

--what Len would spend his life doing and both writing and lecturing about.

We had a prolific correspondence over the years, sharing our work, and happy for the occasions provided by professional activities to get together somewhere every now and so often.

|

| Leonard Pronko conducting a kabuki workshop. |

To my knowledge, the first publication expressing his ideas about kabuki was an interview in

Engekikai, January 1964. I still have that issue and have translated it below, perhaps a bit roughly, but close enough to Len's words to convey their intentions. He appears to have given the interview in both English and Japanese, which surprises me as I wasn't aware that his Japanese at that early stage in his kabuki interests was so advanced.

Pay attention to the interstitial notes of the interviewer, Nagano Reiko, whose reactions to Leonard's obviously enthusiastic discourse show how impressed she was.

|

| Leonard Pronko. |

The pictures below show the cover of Engekikai, January 1964, and the two-page interview itself.

|

| Cover of Engekikai, January 1964, showing Ichikawa Danjūrō as Kumedera Danjō in Kenuki. |

“Foreigners’ Views

of Kabuki:

Leonard Pronko”

Interviewed by Reiko

Nagano

Translated by Samuel

L. Leiter

Engekikai,

January 1964: pp. 110-111

Leonard Pronko: Kabuki is fantastic. Really fantastic. I’ve seen nō and bunraku but I don't think there's anything better than kabuki.

Ever since I arrived in Japan in June I’ve been completely

captivated by kabuki. . . . I’ve been going an average of three times

a month, sometimes as often as five. For example, the recent full-length

production of Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura. . . . I saw a rehearsal, and

then four performances. The next month I went to Nagoya for two days

of kabuki in a row. I’m squeezed into the Kabuki-za from 10:30 a.m. to after 9:00 p.m.

but I just don’t get tired. At night, even when I’m in bed with my eyes

closed, stage scenes flit by my eyes, one after the other. . . . Once I’m caught up

in that world, the dream drama unfolding before my eyes makes me forget everything

else. Kabuki has such a strange attraction and atmosphere, an attraction I don’t

see in Western theatre, so I absolutely must

study it.

[Nagano: He speaks rapidly, his tone passionate from the get-go.

Now and then Mr. Pronko interjects rather good Japanese into the conversation.

A professor of French literature at Pomona College,

California, he focuses on French theatre (while embracing all of Western

theatre) and its mutual relationship with Asian theatre. He currently holds a

Guggenheim Fellowship allowing him to visit Asia to research its theatre in

situ.

He studied at Paris’s famed Charles Dullin École and Théâtre

National Populaire, among other institutions, and became fascinated by kabuki,

so different from Western theatre. He says he plans to publish a book about

kabuki in the near future. He also has directed plays at his college. Mr. Pronko

offered thoughts on kabuki that make him different from all those other foreigners

who recently have suddenly have taken such an interest in kabuki.]

Pronko: There are many Western theatre practitioners, especially

actors and directors, who should be learning from Japanese traditional theatre,

kabuki, noh, and bunraku. The basis of my current research involves pointing

out their particular excellences. To begin with, Western drama tends to be

overly intellectual, and theatregoers are forced to concentrate on the dialogue

and its symbolic meanings.

Kabuki, on the contrary, is filled with a great abundance

of beauties and pleasures. It synthesizes the delights of many stage arts into

a single one. Take, for instance, Senbon Zakura, which skillfully blends

the flamboyant stylization of aragoto acting with the elements of realistic

sewa, everyday-style acting. The gorgeous spectacle of the michiyuki travel-dance scene is matched—in the true sense of the word—by the “dramatic” quality of

the “Tōkaiya” scene. The three components of drama, music, and dance are in perfect

harmony, providing a truly enjoyable experience.

[Nagano: His specialized interests aside, Mr.

Pronko’s deep knowledge and enthusiasm practically bowled me over. Soon, he

spoke of the differences between realism and theatrical stylization.]

Pronko: It’s once again necessary to reconsider

Western realism. In this connection, what we study in kabuki touches the fundamental

nature of theatre. Modern Western theatre usually has pursued realism, seeking

to reproduce the reality of life on stage. However, actuality on stage is no

more than an outline. It’s impossible to put real life on stage. Even so, kabuki,

at first sight having no relation to realism, actually creates a kind of

realism that goes beyond an outline. Through the transcendence of kabuki’s

uniquely stylized acting, so-called realism beautifully enlarges the actuality

of real life, transforming its appearance, and crafting a theatrical reality sublimated

by the stage, which is how I understand it. Since the theory of realism is

transcended, it has no limits in kabuki.

How can this theatrical reality lucidly handle things like complex,

difficult, psychological issues? For example, there’s Matsuō in “Terakoya.” On

the realistic stage, Matsuō’s expressions as he stares at the severed head of

his own son, would seem ridiculously exaggerated. But the exaggerated movements

of his eyes and eyebrows enhance Matsuō’s anguish, making them all the more

powerfully expressive. Ichikawa Danjūrō XI’s Matsuō was exceptional, wasn’t it?

He raised his eyebrows like this, used his eyes like this, raised his voice

like this. . . . (Mr. Pronko demonstrated with considerable facility.)

I think the greatest ingredient in kabuki’s unique arsenal

of stylized acting is the mie pose. The moment a mie performed,

the hero’s expression and state of mind are proportionately enlarged. There’s

no way that Western theatre’s realism can match such overwhelming expressiveness.

The scene when Nikki Danjō rises on the hanamichi in Meiboku Sendai

Hagi’s “Yuka no Shita” scene, or his entrance in that play’s “Ninjō” scene

are classics of this device. I can only imagine how exciting it would be if Shakespeare’s

plays, Macbeth, for example, were to use such stylized kabuki techniques.

It’s easy to understand the emphatic

effect brought to the stage by kabuki’s painted-face makeup (kumadori) and

its elaborate costumes. That is, stylized methods like these bind style and

objective in perfect unity. The actor’s every movement being thus enlarged, he's totally invested, down to his toe-tips, with nothing wasted, his body no

less powerful than his facial expressions. In contrast, the Western actor’s arms

and legs are little more than long, useless appendages.

[Nagano: The more fervently he enthuses about

kabuki, the faster his speech grows. I asked Mr. Pronko, who could talk about

kabuki all day, what it is in kabuki that a foreigner likes, and what obstacles

there are to understanding it.]

Pronko: The language, of course, is a big problem. Even though the way

the actors express themselves and use their costumes during the gidayū narration

and the long scenes of dialogue are understandable, it’s not so easy to

follow the complex situations and the development of the plot. But isn’t that

true for the average Japanese? Performers and aficionados have no problem

following the give and take of the original scripts. They may perversely insist

in sticking to the originals but if the audience can’t understand they’ll

get bored and things will backfire. I wonder what would happen if

they thought about revising the scripts in a way that wouldn’t damage the

originals. A full-length version of Hamlet would take four hours to perform but, according to a director’s interpretation,

it’s normal for it to get shortened to three or three and a half hours. I feel

that this kind of thing is one way that kabuki could learn something from

Western theatre practice.

And what of the objections

to the feudalistic thematic backgrounds? There are many examples, like, for

instance, one motif that's hard to accept as is would be the sacrifice of one’s

own child for the sake of one’s master. I guess you simply have to transcend it. But

the fundamental theme of loyalty and fidelity are universal, and feelings of

anguish, doubt, and sorrow supersede all differences of social systems. The

point is whether or not you can empathize with the drama.

What about the onnagata? This, too, is something representative of what makes kabuki performance

unique and outstanding. Even to eyes that know a man is performing as a woman

there’s absolutely nothing strange about it because, oddly, it makes concrete

the essence of femininity. The other day, when I saw a shinpa performance in which an actress and an onnagata appeared together

on the same stage, I was shocked by the difference in how “woman” was shown.

That’s because the onnagata was rather natural and seemed quite womanish.

The onnagata’s voice is fine, you know. While it’s a

constructed voice you could also say it’s a theatrical voice. (Here he gives his impression of an onnagata’s voice.) In a manner of

speaking, you could think of it as feeling like a piece of ancient, worn-out silk.

[Nagano: Of course, this is Mr. Pronko’s personal

interpretation. I then asked him about his thoughts, critical and otherwise, on

kabuki’s present and future existence.]

Pronko: The new kabuki

plays (shinsaku mono) won’t do. Kabuki has kabuki performance

methods, and there are many fine plays. And kabuki theatregoers want to see “kabuki.” Something creates a desire to do plays that imitate

the methods of modern drama. I can’t help thinking that the staging methods of

recent shinsaku are committing a serious error with regard

to kabuki’s future. I’m not saying that plays dealing with

contemporary issues shouldn't be produced; for example, even Chikamatsu's plays have

realistic aspects and new themes. Nevertheless, they’re performed within the

framework of kabuki tradition. If shinsaku are absolutely necessary, I think this is

how they should be performed.

I hear that the younger

generation is unfamiliar with kabuki, which is really a shame. This superb form

of theatre has been transmitted to us down the years but its value is unknown. When

only the world’s actuality is shown, what happens is that there’s no room to

enjoy the world of drama. One solution is to give kids a chance to experience

kabuki from their childhood on. It’s imperative that the younger generation

knows kabuki and grows up within its atmosphere. This will give birth to a new

life for kabuki. France has a system for introducing classical drama to

children. They may not completely understand it, but they at least acquire a

familiarity with classical drama.

[Nagano: The face of Engekikai’s Tsurumi-san, who was

present, lit up at the mention of a kabuki classroom (kabuki kyōshitsu). . . . . SLL: A regular system of special performances for

schoolchildren was already in place, and continues today.]

Pronko: That’s excellent.

If more assistance could be provided for it, and if there were guidance for

the mutual benefit of the younger generation of actors and audiences, it would really be great for everyone.

[Nagano: Mr. Pronko, who was anticipating the imminent

arrival in Japan of visits by traditional Chinese and Indian performances,

concluded thusly:)

Pronko: How much will Western

theatre, ignorant till now of Eastern theatre, be able to learn from it? In

order to know concretely, nothing’s better than to actually see different types

of theatre. After I return to America, I’m going to look for such opportunities.

I think I want to create plays that use kabuki style, and perform them. The

themes may be my own, but they will make full use of kabuki techniques. I

sincerely hope that they will give rise to theatrical harmony.